During the first eight months of the project, INTEgreat produced an Integration Strategy Framework (ISF), grounded on the experiences of migrants and stakeholders, collected through interviews conducted in the specific local contexts of five European cities: Varese, Limerick, Barcelona, Nicosia and Athens. After the transversal obstacles identified through the country reports, the research conducted for the drafting of the ISF revealed specific obstacles in each of the four INTEgrat thematic areas.

Health

Protection of the right to health in the countries involved in the INTEgreat project is essentially guaranteed, by ensuring healthcare to anyone who needs it, but still shows gaps particularly with regards to the protection of mental health. In addition, some obstacles emerge for some categories of people with a migration background, especially the most vulnerable ones, to whom the medical assistance is generally provided by NGOs. In fact, the access to the healthcare system can be challenging without the official papers and, in particular situations, as in the Greek camps, healthcare services are provided only by organizations having access to them.

One of the most reported aspects concerns the language barrier, both on the part of migrant people who do not speak the language of the host country and on the part of health workers for the use of the lingua franca (English). Some problems encountered in the use of these services are not attributed by migrants to their status, but are seen as problems that affect all citizens. Some of these criticalities are due either to the scarcity of resources or coordination of services. In all countries, difficulties related to the lack of intercultural skills from service providers are reported.

From the interviews with stakeholders, it emerged that health is a dimension in which the services respond quite effectively to the needs of asylum seekers and refugees. Another obstacle noted by stakeholders is the poor or ineffective information provided to the target group that can limit migrant people’s access to health.

Employment, Training & Capacity Building

The voices of migrant people point out that (public and private) employment agencies do not seem to be particularly effective. Sometimes, this problem is reflected in weak job orientation, which does not seem to fill the gaps and needs of migrant job seekers. A malfunctioning emerges in the wide range of services aimed at facilitating the integration of those with international protection into the labor market. In particular, in the first reception (where the stay may last for years) there is scarce information on employment and training services.

Despite the key role that language (L2) plays in the employment recruitment process and in accessing other integrated services, some interviewees report few or no opportunities to learn a second language or to take training courses to be more competitive in the local labour market. Language is one of the main cross-cutting barriers to accessing employment along with bureaucratic problems related to the legal status of people with a migration background. This issue often intersects a large gap in the recognition of qualifications, skills and previous experience. Formal education does not always cooperate with non-governmental actors to offer teaching/training packages for the integration of the target group, helping them to bridge the gap between their education and the labour market.

Moreover, the migrant people’s point of view highlights that there are few opportunities to “re-train and upskill”. Meanwhile, in the absence of “re-training and upskilling services” and to react to the related risk of unemployment, the network of relationships remains the main bridge to the job market. While this network is positive in that it allows a gateway to the labour market, on the other hand, it may limit the opportunity for self-empowerment and the social inclusion process in host societies.

Concerning the possible institutional reactions to these obstacles and the identification of “new” training proposals, the emphasis is on the supportive role of third sector organizations, which in many cases not only publicize training opportunities to migrants but also contribute to the financing (or identification of sponsors) of their implementation. In this regard, we find possible suggestions from the migrants who had training experiences. Specifically, we find references to some satisfying training opportunities and internship periods as incoming gateway/integration into the job market. In this case, the implementation of internships and training courses recalls the importance, previously mentioned and common to all countries, to make the training services more consistent with the employment area.

Alongside the satisfaction of these types of experiences, it is possible to remark also a less favourable note with the implicit claim of a lack of stakeholder partnerships and a failure in disseminating good practices. Two further and final obstacles that emerged from the interviews are, on the one hand, the greater difficulty of placing migrant women, especially if single mothers, and on the other, the significant barriers in accessing the labour market for those with complex personal-psychological conditions. In the first case, this seems to be linked to women’s difficulties in attending language courses due to the lack of a safe space (and resources) where they can leave their children. The second case again suggests a lack of stakeholder partnerships enabling to cope with the several dimensions of an integration process. In conclusion, with regards to employment, the stakeholders interviewed emphasize the difficulties companies face in employing asylum seekers and refugees.

A first problem concerns the lack of information on these subjects, on their rights, on the documents/status they must have in order to be hired and work, on the duration of their documents and of their stay in the country. Another bureaucratic barrier to accessing the labour market (but also to renting/buying a house and other aspects of integration) is the difficulty, due to the same lack of information that characterizes companies, of asylum seekers and refugees to open a bank account.

According to some interviewees, keeping migrant people in irregular working conditions may be functional to the vested interests of entrepreneurs.

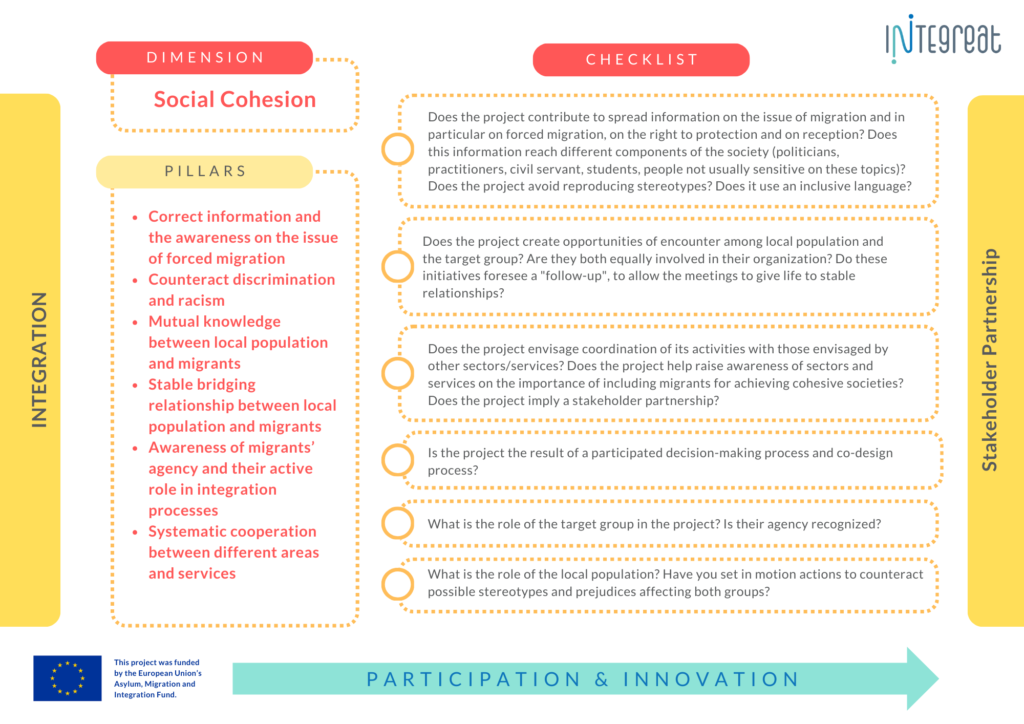

Social Cohesion

For the target groups of INTEgreat, relations with the local population represent a source of information, and therefore a resource, for accessing opportunities and services. However, the interviews (both with migrant people and stakeholders) reveal a scarcity of this type of relationship. The relationships built by migrants in the host country seem to be mostly with people of the same nationality or with people who have shared the reception experience in the host country.

Even if there is no evident problem at territorial level, most of the migrants do not have any relationship with the local population and therefore cannot be considered fully integrated. In the absence (or scarcity) of relations with the local population outside of the reception system, it is therefore compatriots, people of the same nationality and civil society organizations that deal with hospitality, who represent a point of reference for migrants and especially newcomers.

Work, training and volunteering experiences are reported as situations in which friendly relationships take shape even with members of the local community. These relations then translate into support in accessing some services, but also into a feeling of “feeling welcomed”, which recalls social cohesion.

From interviews with people with a migration background, it emerged that relations with the local community, although viewed positively and “desired”, remain the most difficult to build, also due to perceived attitudes ranging from distrust to racism.

Misinformation on the issue of migration and the manipulation of this issue in public discourse (by politicians and media) are, according to the interviewees, at the origin of the behaviors of the local population (including service providers) ranging from distrust, to racism and discrimination. The lack of mutual knowledge and the presence of prejudices represent an obstacle to “bridging” relationships and to a cohesive society.

All interviewees agree on the usefulness of public events (cultural, sports, recreational …) to facilitate gatherings between the local population and migrant communities. Events of this kind are already often organized in the contexts of the interviewees; however two limits emerge. The first is that migrant people often do not have an active role in the organization. The second is that these events do create contact, but do not give rise to the construction of deep and lasting relationships.

Social cohesion not only deals with migration. Conversely, at the institutional level, the issue of migration and in particular the aspect of hospitality, is considered and treated as separate from the different areas in which public policies and services operate. This element emerges from the interviews as an absence (or scarcity) of coordination between different actors and different levels of integration.

Together with limited coordination, the interviews also highlight a limit in the participation the various actors have in the design, as well as in the implementation of policies. Furthermore, among these actors, migrants are often not mentioned: a symptom there is still a prevailing vision that sees them as beneficiaries of reception rather than co-protagonists of their integration processes.

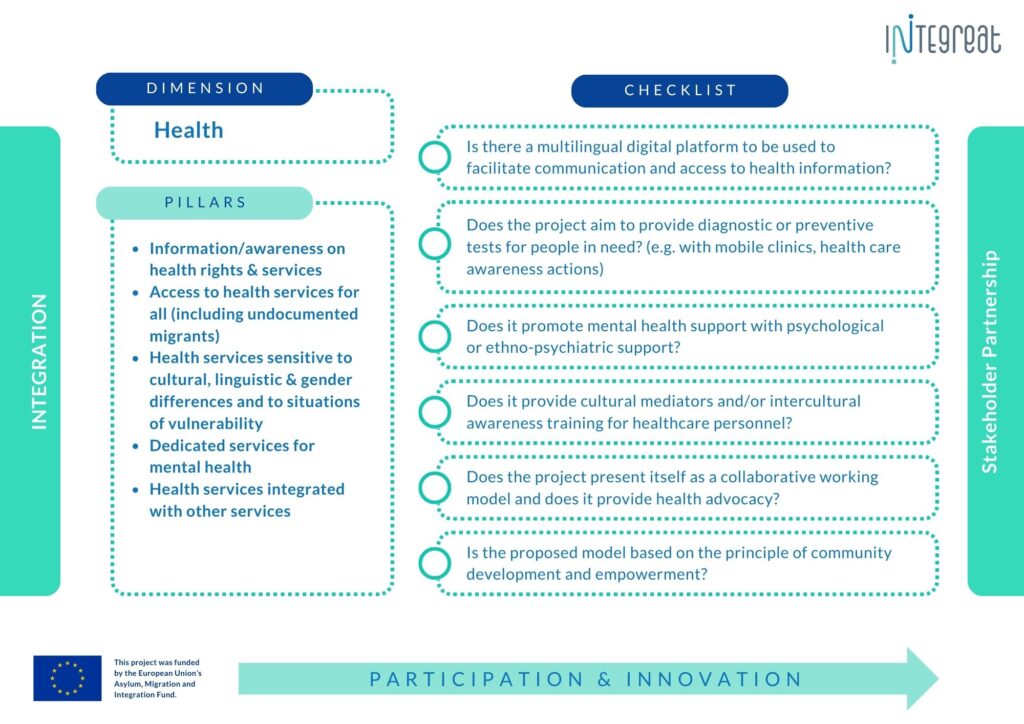

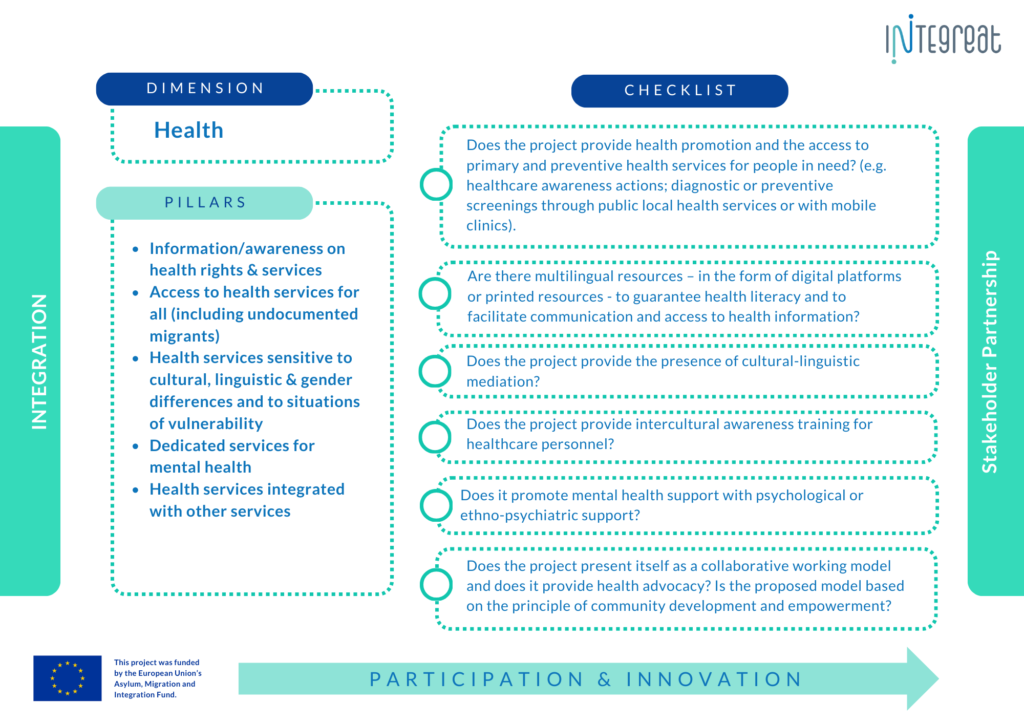

INTEgreat guidelines for integration

To face the above-mentioned obstacles identified through our work in the project, INTEgreat offers in its Integration Strategy Framework a set of recommendations. From the operational point of view these recommendations have been translated into guidelines: a practical and user-friendly tool to verify the consistency of the pilots carried out within the INTEgreat project according to the principles of the ISF, but which can also be applied outside the project, for other initiatives aimed at integration in Europe. In fact, the guidelines summarize, for each of the four thematic areas of integration considered by the INTEgreat project (health, employment, training & capacity building, social cohesion), the principles that support it (pillars). Next to the pillars, the project partners will find a checklist helping them to design pilots and consider from the very beginning all the elements that have been recognised as key in the achievement of full integration in the thematic area(s) impacted by the pilot. The ISF Guidelines are contextualized within the conceptual framework at the heart of the INTEgreat project: integration, stakeholder partnership, participation and innovation.

In the following infographics, the relationship between these concepts is represented graphically: in the card of each thematic area, integration is the first concept we find (on the left), as the general objective of the pilots. Stakeholder partnership is the second concept (on the right) that supports the framework, as the approach that should characterize the pilots. Finally, participation and innovation (at the base of the framework), as principles underlying the integration process, are necessary for an effective stakeholder partnership and for the sustainability of the pilots (represented by the actual change achieved by the project).

The cards that make up the guidelines have been conceived as a visual and quick reminder to be considered by the partners in the design of the pilots, but also in their implementation as they are based on empirical data that present the specific obstacles, challenges and best practices existing in their own contexts.

For this reason, it is worth to underline that the present guidelines do not claim to be exhaustive with respect to the conditions that favour integration, but are specifically targeted to the European context in which the pilot projects are developed.

Previous version of the Checklists